Acknowledgment of Country

Awabakal People and Buttaba – We acknowledge the Awabakal and Worimi peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Buttaba and the Lake Macquarie region stand. We pay our deepest respects to their Elders past, present, and emerging, and extend this respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The Awabakal people’s enduring connection to this land spans over 11,800 years, a profound relationship that reflects a deep understanding of the environment, its stories, and its sacred significance. Their heritage continues to shape the identity of this region, reminding us of the responsibility to care for the land, waters, and skies as they have done for millennia.

Buttaba

Nestled on the western shores of Lake Macquarie lies the suburb of Buttaba, a place enriched by a legacy that predates written history. For at least 11,800 years—since the end of the last Ice Age—the Awabakal people have called this land home, living in harmony with its resources and preserving their culture through stories, language, and sustainable practices.

The name Awabakal comes from “Awaba,” meaning “a plain surface,” referring to the calm expanse of Lake Macquarie. This lake was a cornerstone of their culture, offering sustenance, spiritual meaning, and inspiration for their Dreamtime stories.

By exploring the rich history of the Awabakal people and the cultural significance of Buttaba, we gain a deeper appreciation for the heritage that continues to shape this beautiful region today.

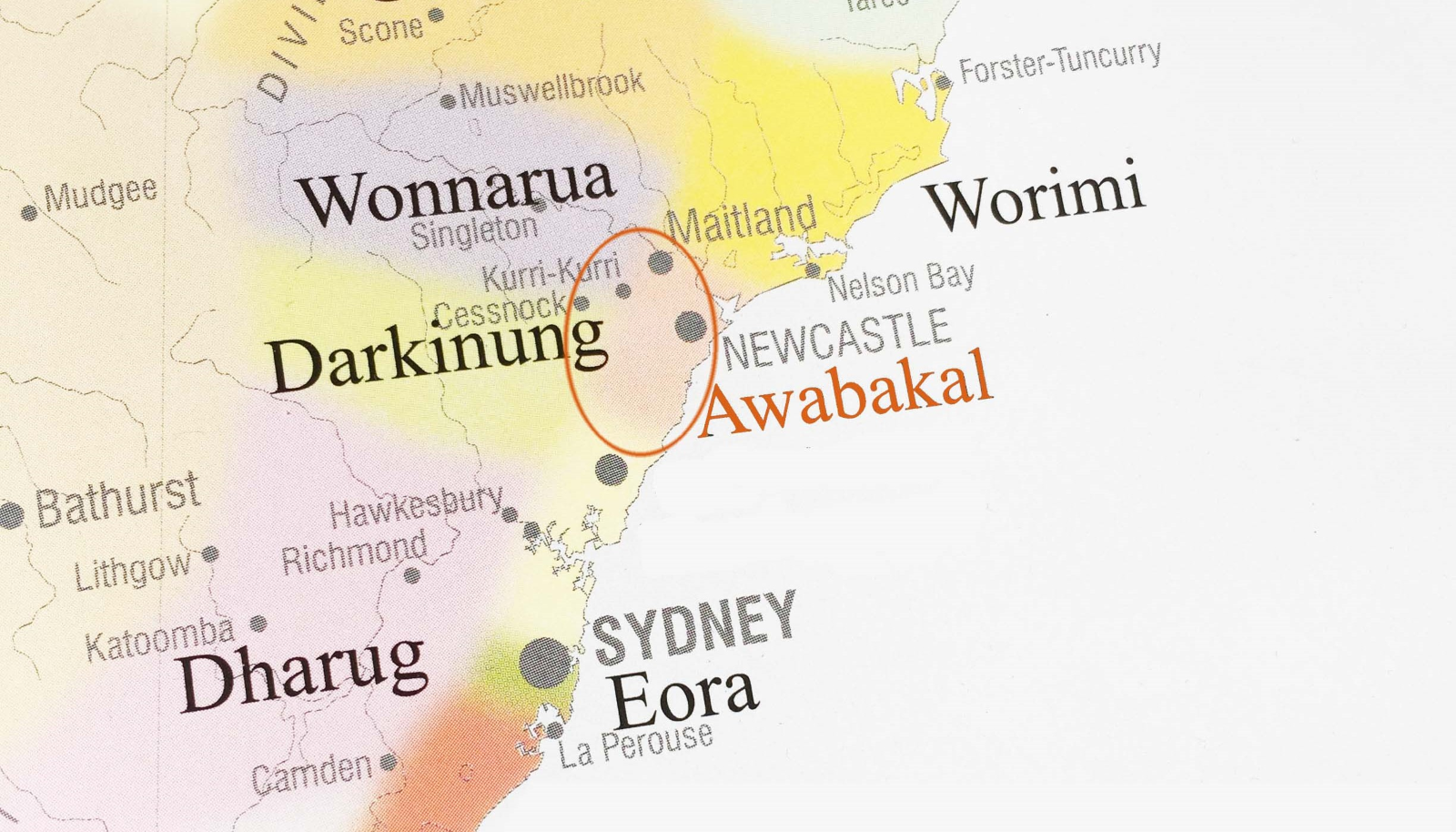

Mapping and Custodianship of the Awabakal Lands

The Awabakal people were skilled custodians of a diverse region that extended from Port Stephens in the north to the southern shores of Lake Macquarie. Their land included rich coastal environments, forests, plains, and waterways, which they managed sustainably for thousands of years (Awabakal History).

Unlike Western concepts of ownership, the Awabakal viewed the land as a shared entity, deeply spiritual and interconnected with all aspects of life. Every feature of the landscape, from hills to waterholes, was imbued with meaning, and these places were mapped and remembered through oral traditions and Dreamtime stories.

Custodianship was not about possession but about responsibility. The Awabakal employed techniques such as cultural burning, which not only encouraged new plant growth but also reduced the risk of destructive wildfires. This practice, recognised today as a highly effective land management strategy, reflects their deep understanding of the environment (examples of reconciliation).

The arrival of European settlers disrupted this balance. The introduction of agriculture, land clearances, and property divisions disregarded the Awabakal’s traditional boundaries, severing their cultural and spiritual ties to the land. Despite these challenges, the Awabakal people continue to fight for recognition of their custodianship through initiatives like Native Title claims, which aim to restore their rights to significant areas of their ancestral lands.

Awabakal Language: A Lingering Legacy

The Awabakal language is a vital thread in the cultural fabric of the Awabakal people. Like many Aboriginal languages, it is intricately tied to the land, with words and phrases reflecting their deep connection to the environment. For instance, the word “Awaba,” meaning “a plain surface,” describes the tranquil waters of Lake Macquarie, which are central to their identity (Awabakal language history).

Although colonisation led to the near extinction of the Awabakal language, it has not been forgotten. Efforts to revive it began in the 19th century with the work of Reverend Lancelot Threlkeld, who documented the language extensively in collaboration with Awabakal leader Biraban. Today, these records are being used by linguists and cultural leaders to reconstruct and teach the language (language revival efforts).

Revival projects, such as those led by the Awabakal Language Revival Project, focus on making the language accessible to the community. Resources like educational workshops and online tools are helping to pass down knowledge to younger generations. Words and phrases such as “ngyia yirrikarna” (I am happy) and “wangyarra” (place of rest) reflect the richness of this heritage.

Through these ongoing efforts, the Awabakal language is more than a remnant of the past—it is a living testament to the resilience of a people determined to keep their culture alive.

Dreamtime Stories Of The Awabakal Tribe

The Dreamtime stories of the Awabakal people reflect their profound spiritual connection to the land and its features, each tale carrying lessons about harmony, respect, and responsibility.

One of the most famous stories is that of Tiddalik, the Greedy Frog, a giant frog who, overwhelmed by thirst, drank all the water in the land, causing a severe drought. The other animals, desperate to save their environment, devised a plan to make Tiddalik laugh. Their playful antics succeeded, and as Tiddalik burst into laughter, all the stored water was released, replenishing the rivers and lakes. This tale, documented in resources like the Awabakal Language Project, teaches the value of sharing and the dangers of hoarding resources.

Another story recounts the legend of Malangbula, where two women were turned to stone at Swansea Heads as a punishment after a disagreement with an Awabakal warrior. Today, the two upright rock formations at Swansea Heads are said to represent these petrified women, serving as a visible reminder of the story. The significance of this site is detailed on the Awabakal cultural stories page.

The story of When the Moon Cried explains the creation of Belmont Lagoon. Feeling neglected, the Moon ascended higher into the sky and began to cry, its tears forming the lagoon below. When the people expressed their joy and gratitude for the new water source, the Moon felt appreciated, leading to the full moon phases celebrated by the Awabakal people. This narrative is also shared on the Awabakal Language website.

The Awabakal people have a Dreamtime story about How Coal Was Made. According to their lore, a volcanic eruption during the Dreaming at Redhead created coal, a resource now vital to the region. This story ties the natural resource to the area’s spiritual and historical roots, as described on the Awabakal storytelling resource.

Daily Life and Practices of the Awabakal People

The daily life of the Awabakal people revolved around a deep understanding of their environment, guided by seasonal patterns and a sustainable approach to using natural resources. Each activity reflected a connection to the land and a respect for its offerings.

The waters of Lake Macquarie, or “Awaba,” were vital for fishing and gathering shellfish, which formed a significant part of their diet. Fishing was often done using bark canoes crafted from local trees, which allowed access to the lake’s abundant marine life. Shell middens found along the lake’s shores today are a testament to this long-standing reliance on aquatic resources, as highlighted in the Awabakal cultural records.

In the surrounding bushlands, the Awabakal people hunted kangaroos, wallabies, and possums, using tools like spears and boomerangs. They also foraged for fruits, nuts, and roots, particularly those native to the region, such as wattleseed and yam daisies. These practices ensured a varied and nutritious diet while preserving the ecosystem’s balance.

A standout feature of their land management was cultural burning. This practice involved carefully controlled fires to clear undergrowth, promote plant regeneration, and attract grazing animals. Today, this ancient technique is being recognised and reintroduced as an effective way to manage land and reduce the risk of bushfires, as noted by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Community life was tightly knit, with clearly defined roles. Elders held a revered position, acting as leaders, storytellers, and the keepers of cultural knowledge. They guided decision-making, ensured traditions were passed down, and resolved disputes within the group.

Education among the Awabakal people was oral and practical. Young members of the community learned through observation, storytelling, and direct participation in activities such as crafting tools, hunting, and performing ceremonial duties. This intergenerational transmission of knowledge ensured cultural continuity and a deep-seated understanding of their responsibilities toward the land.

The Awabakal way of life offers timeless lessons about sustainable living and community harmony, principles that are gaining renewed attention in contemporary environmental and cultural discussions.

A History of Violence and Loss

The arrival of European settlers in the late 18th century brought devastating changes to the lives of the Awabakal people. The introduction of colonial policies, land clearances, and violent confrontations disrupted their cultural practices, displaced their communities, and caused immeasurable loss.

One of the most harrowing aspects of this period was the massive displacement of Aboriginal people from their ancestral lands. The fertile areas surrounding Lake Macquarie, which had sustained the Awabakal for millennia, were taken over for farming and settlement. Traditional boundaries and sacred sites were disregarded, severing the Awabakal people’s spiritual connection to their land.

Disease also played a significant role in the decline of the Awabakal population. Epidemics of smallpox and influenza, introduced by settlers, spread rapidly through Aboriginal communities, who had no immunity to these foreign illnesses. The combination of disease and malnutrition decimated the population, as recorded in the Awabakal Language History.

Violence during this period further compounded the suffering of the Awabakal people. Historical accounts detail conflicts and massacres, as settlers sought to control land and resources. Despite this, there are also stories of resistance and resilience, with Awabakal leaders such as Biraban working to preserve their culture and advocate for their people.

The cultural loss extended beyond land and population. The forced removal of children, now known as the Stolen Generations, disrupted family units and led to the erosion of traditional knowledge and practices. This painful chapter is a lasting scar in Australia’s history, with ongoing efforts to reconcile and heal these wounds.

Today, initiatives such as Native Title claims and community-led heritage projects aim to restore some of what was lost. These efforts not only seek to protect what remains of Awabakal culture but also to educate others about the history and significance of this resilient community.

The history of violence and loss experienced by the Awabakal people is a reminder of the importance of recognising and addressing the injustices of the past, ensuring they are never forgotten.

Native Title and Land Rights

The struggle for recognition and the restoration of land rights has been an ongoing challenge for the Awabakal people. Native Title, introduced under the Native Title Act of 1993, provides a legal framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to claim rights to land and waters based on traditional laws and customs. For the Awabakal, this process is both a tool for justice and a means of reconnecting with their ancestral lands.

The lands traditionally managed by the Awabakal people spanned from Port Stephens to the southern shores of Lake Macquarie. Over time, colonisation disrupted their ability to access and care for these areas. Despite this, the cultural connection to the land has remained strong, forming the foundation for modern Native Title claims. The Awabakal Local Aboriginal Land Council, established in the 1980s, plays a vital role in advocating for land rights and protecting culturally significant sites.

One of the key aspects of Native Title is proving an unbroken connection to the land, which can be challenging due to the displacement and loss caused by colonisation. The Awabakal people have demonstrated resilience in preserving their oral histories, traditions, and cultural practices, all of which support their claims. According to the National Native Title Tribunal, Native Title claims involve extensive documentation, collaboration with government agencies, and community engagement.

In addition to Native Title claims, the Awabakal people engage in co-management agreements with local councils and conservation organisations. These partnerships ensure that sacred sites and culturally significant areas, such as those around Lake Macquarie, are protected and respected.

While Native Title does not fully compensate for the injustices of the past, it represents a step toward reconciliation and the recognition of Aboriginal sovereignty. For the Awabakal people, land is not merely a resource but a living connection to their ancestors, culture, and spirituality. Restoring access to these lands is a powerful act of healing and empowerment.

Reconciliation Efforts and Cultural Preservation

In recent decades, reconciliation efforts have gained momentum, creating pathways for healing and mutual understanding between the Awabakal people and the broader Australian community. These initiatives aim to honour Aboriginal heritage, restore cultural practices, and address the injustices of the past.

A cornerstone of these efforts is the revitalisation of Awabakal language and traditions, supported by community organisations such as the Awabakal Local Aboriginal Land Council. Language revival projects, educational workshops, and cultural festivals help reconnect the Awabakal people with their heritage while fostering broader awareness of their contributions to the region (Awabakal Land Council).

Education plays a critical role in reconciliation. Programs such as the Awabakal Preschool integrate Aboriginal cultural knowledge into the curriculum, teaching children about Dreamtime stories, traditional practices, and the importance of sustainability. This approach not only preserves cultural knowledge but also instils pride in Aboriginal identity among the younger generation.

Collaborative projects between local governments and the Awabakal community have also led to the recognition and protection of sacred sites, such as those around Swansea Heads and Belmont Lagoon. These efforts ensure that important cultural landmarks are preserved for future generations while raising awareness of their significance among non-Indigenous Australians.

Art and storytelling are powerful tools in reconciliation. Events like the Lake Macquarie Aboriginal Heritage Celebration bring together Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities to share traditional dances, songs, and artworks. These gatherings create a space for dialogue, respect, and shared appreciation of Aboriginal culture.

Despite these advancements, reconciliation remains an ongoing process. Challenges such as systemic inequities, gaps in public awareness, and limited resources for cultural preservation highlight the need for sustained efforts. However, the resilience and determination of the Awabakal people continue to inspire progress toward a more inclusive and respectful society.

Awabakal Art and Cultural Expressions

The Awabakal people’s artistic expressions are vividly reflected in their rock engravings, which are significant cultural sites within the Lake Macquarie region. Notable locations include areas around Swansea Heads and the Munmorah State Conservation Area, where engravings depict animals, human figures, and spiritual symbols. These sites offer insights into the Awabakal’s rich cultural heritage and their deep connection to the land. It is essential to respect the cultural significance of these sacred places, as noted by the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage.

For those interested in contemporary Awabakal art, the Museum of Art and Culture yapang in Booragul is a premier destination. The museum hosts a dedicated Aboriginal program called ‘yapang,’ meaning “journey/pathway” in Awabakal, which features contemporary Aboriginal art and related programming year-round. Exhibitions often showcase works by emerging and established First Nations artists, celebrating the ongoing cultural journey of the Awabakal people through venues like the Museum of Art and Culture.

Additionally, the Multi-Arts Pavilion, mima at Speers Point provides an engaging space for Aboriginal art exhibitions. The name ‘mima,’ meaning “cause to stay” in Awabakal, reflects the venue’s mission to immerse visitors in art experiences that highlight the rich cultural narratives of the Awabakal people. Learn more about these exhibitions at the Multi-Arts Pavilion.

Prominent Figures in Awabakal History

The Awabakal people’s history is brought to life through the extraordinary contributions of individuals like Biraban, a 19th-century Awabakal leader and interpreter. Biraban, whose name means “eaglehawk,” was a revered figure known for his wisdom and linguistic talents. He worked alongside Reverend Lancelot Threlkeld, helping to document the Awabakal language, one of the first recorded Aboriginal languages in Australia (Awabakal Language History).

Biraban’s leadership extended beyond language preservation. He played a crucial role in fostering cross-cultural understanding during a period of significant upheaval. Acting as a mediator, Biraban translated and interpreted for both Aboriginal and European communities, navigating the complexities of two worlds with dignity and skill. His efforts to preserve his people’s knowledge and traditions ensured that Awabakal culture would not be forgotten, even as colonial pressures mounted.

Today, Biraban’s legacy is honoured through various initiatives, including language revival projects and the naming of schools and community spaces. His work continues to inspire not only the Awabakal community but all Australians who value the importance of cultural preservation.

Modern leaders within the Awabakal community build upon Biraban’s foundation. Members of the Awabakal Local Aboriginal Land Council work tirelessly to protect sacred sites, advocate for Native Title claims, and promote the well-being of their people. Meanwhile, Awabakal artists and educators share their culture through storytelling, art, and public engagement, ensuring that the next generation remains connected to their heritage.

Exploring Buttaba Today

The suburb of Buttaba, located on the western shores of Lake Macquarie, offers a unique blend of natural beauty and historical significance. Its name, believed to have roots in the Awabakal language, reflects the deep connection of the Awabakal people to this land. Although modern development has reshaped the area, the spirit of its Aboriginal heritage remains an integral part of its identity.

One of the standout features of Buttaba is its proximity to Lake Macquarie, known as Awaba by the Awabakal people. The lake continues to serve as a focal point for both residents and visitors, offering opportunities for fishing, boating, and enjoying the tranquil waters. For the Awabakal, this area was more than a resource; it was a spiritual sanctuary, and their stories and traditions continue to highlight its significance (Lake Macquarie History).

Visitors to Buttaba can explore its historical and cultural ties through nearby landmarks and walking trails. The area’s connection to Aboriginal heritage is acknowledged through interpretive signage, community events, and educational initiatives. Local schools and community groups often host workshops and programs designed to share the stories and traditions of the Awabakal people.

As Buttaba continues to grow, its Aboriginal heritage serves as a reminder of the importance of preserving cultural identity while embracing progress. The balance between history and modernity makes Buttaba a unique and meaningful place to explore, offering both natural beauty and a deep cultural narrative.

The Awabakal and Lake Macquarie: A Living Connection

For the Awabakal people, Lake Macquarie, known to them as “Awaba,” was a vital part of life—both a resource and a spiritual landmark. Its calm waters provided an abundance of fish and shellfish, while its shores offered fertile ground for gathering plants and conducting ceremonies. The lake’s reflective surface inspired many Dreamtime stories, grounding it as a place of cultural and spiritual significance.

Even today, the lake continues to embody this heritage. Walking trails, such as those in the Awabakal Nature Reserve, feature interpretive signage that shares stories about the region’s history and ecology. These trails are part of ongoing efforts by groups like the Awabakal Land Council and Lake Macquarie City Council to educate the public about the lake’s significance and its original custodians.

Beyond its cultural role, Lake Macquarie remains a model for sustainable practices. For generations, the Awabakal people used techniques like cultural burning to manage the surrounding landscape, preventing overgrowth and enriching the soil. Today, these methods are gaining recognition as essential tools for modern conservation, particularly in fire-prone areas (ABC article on cultural burning).

Visitors to the lake, whether fishing, kayaking, or simply enjoying its scenic beauty, are encouraged to reflect on its layered history. By learning about and respecting the Awabakal people’s enduring relationship with this land, we can better appreciate the lake as both a natural and cultural treasure.

Efforts to protect the lake’s ecosystems also echo the practices of the Awabakal people, who used sustainable methods like cultural burning to ensure the health of the environment. These techniques, now being reintroduced, are part of a broader recognition of Aboriginal ecological knowledge as vital to modern conservation efforts (Cultural Burning Practices).

With Respect to the Awabakal People

Writing about the history, culture, and connection of the Awabakal people to Lake Macquarie and the suburb of Buttaba is not just an exercise in research—it’s an opportunity for reflection. The richness of their stories, from Dreamtime legends like Tiddalik to the leadership of figures like Biraban, offers an invaluable lens into the resilience and wisdom of one of the oldest living cultures on Earth.

As someone engaging with this history, it’s impossible not to feel a sense of responsibility. The colonisation of this land brought profound loss, from displacement to cultural erosion, and these scars remain a part of Australia’s story. Learning about the Awabakal people challenges us to confront this legacy and consider our role in fostering understanding and reconciliation.

For me, the process of exploring this topic has underscored the importance of preserving Aboriginal languages, traditions, and land management practices. Cultural burning, for example, isn’t just a historical footnote—it’s a practice with real-world applications today, capable of reducing bushfire risks and regenerating ecosystems. This knowledge, rooted in thousands of years of observation and care, is something we should cherish and respect.

Visiting places like Buttaba or Lake Macquarie allows us to engage directly with this heritage. From walking the trails of the Awabakal Nature Reserve to seeing art that celebrates their culture, these experiences remind us of the ongoing contributions of the Awabakal people. But this respect must extend beyond visits—it requires action, like supporting initiatives led by Aboriginal communities or advocating for the protection of sacred sites.

Ultimately, understanding the Awabakal people’s history isn’t about looking backward—it’s about recognising how their wisdom can guide us in the present. Whether it’s through reconciliation efforts, education, or conservation, every step we take to respect and celebrate their culture is a step toward a more inclusive future.

Awabakal People and Buttaba

1. Who are the Awabakal people?

The Awabakal people are the traditional custodians of the land encompassing Lake Macquarie, Newcastle, and parts of the Hunter Valley. Their history dates back at least 11,800 years, and their culture is deeply tied to the land, waters, and skies of the region.

2. What is the meaning of ‘Awaba’ and its connection to Lake Macquarie?

‘Awaba,’ meaning “a plain surface,” is the Awabakal name for Lake Macquarie. It reflects the calm and expansive waters of the lake, which were central to their culture, providing both sustenance and spiritual significance.

3. What are some of the Awabakal Dreamtime stories?

The Awabakal people have many Dreamtime stories, including the tale of Tiddalik the Greedy Frog, who drank all the water in the land, and the story of Malangbula, which explains the petrified women at Swansea Heads. These stories convey cultural values and explain natural phenomena.

4. Where can I see Awabakal cultural heritage today?

You can explore Awabakal heritage at sites like the Awabakal Nature Reserve and Swansea Heads, which feature interpretive trails and engravings. Art exhibitions at the Museum of Art and Culture yapang in Booragul and the Multi-Arts Pavilion, mima at Speers Point also showcase contemporary Awabakal art and storytelling.

5. How can I support reconciliation and the preservation of Awabakal culture?

Supporting reconciliation efforts can include learning about Awabakal history, visiting cultural sites respectfully, attending events that celebrate Aboriginal heritage, and advocating for the protection of sacred lands. Donations to organisations like the Awabakal Local Aboriginal Land Council also help preserve and promote their culture and rights.