Acknowledgment of the Worimi People and Their Connection to Buttaba

Worimi People and Buttaba – We respectfully acknowledge the Worimi and Awabakal peoples as the Traditional Custodians of the land, including the areas of Buttaba and Lake Macquarie. We pay our respects to their Elders past, present, and emerging, recognising their enduring connection to this land, its waters, and skies. Their stewardship, wisdom, and traditions continue to guide and inspire us.

On the western shores of Lake Macquarie, the suburb of Buttaba holds a shared cultural significance for the Worimi and Awabakal peoples. For thousands of years, the Worimi people have cared for the land, waters, and skies of this region, with their deep connection reflected in their stories, traditions, and spiritual practices.

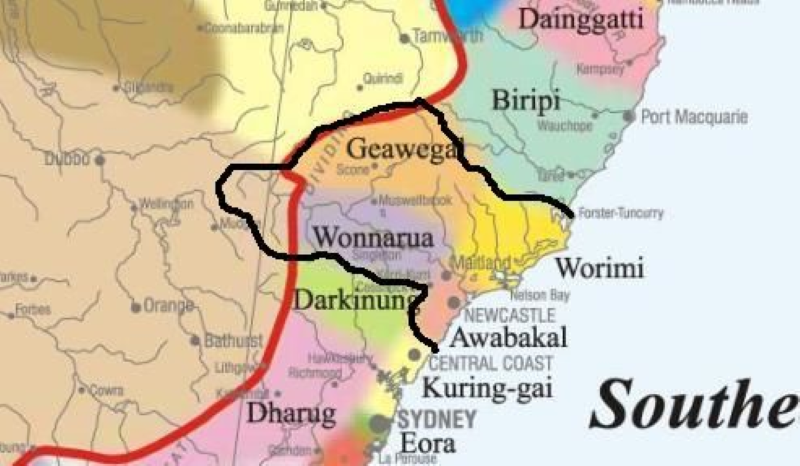

The Worimi people’s custodianship extends across coastal New South Wales, covering regions north of the Hunter River and south of the Manning River. This territory overlaps with the lands of the Awabakal people, exemplifying a history of shared stewardship and mutual respect. In areas like Lake Macquarie and Buttaba, their interwoven cultural heritage reminds us of the importance of understanding and preserving Aboriginal history.

Ancient Custodians of Coastal New South Wales

Timeline of Worimi Settlement

The Worimi people have lived in coastal New South Wales for at least 11,000 years, with archaeological evidence indicating a continuous connection to this land since the end of the last Ice Age. This timeline makes the Worimi one of the oldest living cultures in the world, with their traditions, practices, and knowledge shaped by thousands of years of observation and adaptation to the natural environment.

Overview of Traditional Territory

The Worimi’s traditional territory spans a large area, stretching from the Hunter River in the south to the Manning River in the north, and westward to the Barrington Tops and Paterson/Allyn Rivers. These natural features not only defined the boundaries of their land but also provided vital resources, including fish, fresh water, and fertile grounds for gathering native plants. Significant locations within this territory include Port Stephens, Forster, and parts of the Great Lakes region, each with its own cultural and spiritual importance (Worimi Conservation Lands).

Shared Custodianship with the Awabakal People

Collaborative Practices and Trade

The Worimi people shared borders with neighbouring nations, including the Awabakal Nation to the south. This proximity fostered a history of mutual respect and cooperation. The two nations traded goods such as shell tools, ochre, and food, strengthening their relationship and ensuring access to resources that may have been scarce within their own territories.

Shared Cultural Values

Both the Worimi and Awabakal peoples held a deep connection to Lake Macquarie, known as Awaba to the Awabakal. This shared resource was a focal point of life, offering sustenance and serving as a spiritual hub for both nations. Their cultural values overlapped in areas such as sustainable land management, Dreamtime storytelling, and their reciprocal relationship with the environment.

Connection to Shared Land, Including Buttaba

The suburb of Buttaba, located on the western shore of Lake Macquarie, exemplifies the shared custodianship of the Worimi and Awabakal peoples. Both nations utilised this land for fishing, hunting, and ceremonies, recognising its spiritual and practical significance. The area’s natural features—calm waters, fertile wetlands, and abundant wildlife—reflect the environmental knowledge and collaboration between the two groups.

The Gathang Language

The Importance of Gathang

The Gathang language was traditionally spoken by the Worimi people, as well as neighbouring nations such as the Birpai and Gringai peoples. Gathang is much more than a method of communication—it embodies the knowledge, stories, and cultural identity of its speakers. The language reflects the Worimi people’s deep connection to the land, with specific words tied to features of their environment, such as rivers, plants, and animals.

For example, the name “Gathang” itself is a term used to describe a way of speaking. Words like “Girawin” (kangaroo) and “Buba” (father) carry meanings that connect directly to the everyday life and kinship systems of the Worimi people (Worimi Language Resource).

Revitalisation Efforts

Like many Aboriginal languages, Gathang faced significant challenges due to colonisation and the forced removal of Aboriginal children during the Stolen Generations. By the 20th century, Gathang was in danger of being lost entirely. However, recent efforts to revitalise the language have seen success, thanks to the dedication of Worimi Elders and community leaders.

Organisations like the Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council have worked to record and teach the language through programs in schools, community workshops, and online resources. Tools like the Gathang Dictionary and interactive language apps are also helping to bring Gathang back to life, providing accessible ways for younger generations to reconnect with their heritage.

Connection to Cultural Identity

The resurgence of Gathang has had a profound impact on the Worimi community. By learning and using their language, the Worimi people are reconnecting with their traditions and reasserting their cultural identity. The preservation of Gathang ensures that the knowledge, values, and stories of the Worimi people can be passed down to future generations, enriching the cultural landscape of Australia.

Cultural Practices and Beliefs

Dreaming Stories and Spiritual Beliefs

The Worimi people’s worldview is deeply rooted in the Dreaming, a spiritual framework that explains the creation of the land, its features, and the laws that guide life. Dreaming stories are not just myths—they are lessons that teach respect for the environment, kinship, and the interconnectedness of all living things.

One significant Worimi Dreaming story involves the creation of the Stockton Bight Sand Dunes, one of the largest dune systems in the Southern Hemisphere. According to the story, ancestral spirits shaped the dunes as they moved across the land, leaving behind the rolling sands as a reminder of their journey. These dunes remain a sacred site for the Worimi people and are considered a living testament to their ancestors (Worimi Conservation Lands).

The Willy Wagtail (gitjarrgitjarr) also plays an important role in Worimi spiritual beliefs. This small bird is seen as a messenger and a watcher, warning people of approaching danger or guiding them during difficult times. The bird’s presence in Dreaming stories highlights its symbolic role within the Worimi culture.

Daily Life and Traditional Practices

The daily practices of the Worimi people were closely tied to the rhythms of the natural world. Coastal areas provided abundant resources for fishing and gathering shellfish, which were harvested using traditional methods such as fish traps and spears. The remains of shell middens along the coastline are evidence of these sustainable practices, offering a glimpse into thousands of years of cultural continuity.

Hunting and foraging also played a central role in Worimi life. Inland, they hunted kangaroos, wallabies, and other animals, while gathering bush foods like yams, berries, and wattleseed. Tools and weapons such as boomerangs, spears, and stone axes were crafted with precision, reflecting a deep understanding of the environment and its resources.

Ceremonies and rituals were another vital aspect of daily life. These gatherings often involved storytelling, song, and dance, allowing the Worimi people to honour their ancestors, share knowledge, and strengthen their community bonds. Each ceremony was tied to specific places and seasons, ensuring a cyclical relationship with the land.

Integration with European Settlement

Early Contact and Its Impact

The arrival of Europeans in the late 18th century marked a significant turning point for the Worimi people. In 1791, British colonists began expanding into coastal New South Wales, including Worimi lands. Early contact was marked by mutual curiosity, with the Worimi people initially interacting with settlers through trade and the sharing of local knowledge. However, this relationship quickly shifted as colonisation intensified.

By the early 19th century, the establishment of the Australian Agricultural Company (AAC) in the Port Stephens region had devastating consequences for the Worimi people. Large tracts of land were taken over for farming, displacing Aboriginal communities and severing their connections to sacred sites and hunting grounds. The AAC’s monopoly on land and resources pushed many Worimi people to the fringes of their traditional territory, leading to significant disruption in their way of life (Worimi Conservation Lands).

The introduction of European diseases such as smallpox further decimated the Worimi population, who had no immunity to these illnesses. Alongside the loss of land and cultural practices, disease accelerated the decline of the Worimi people’s population in the early colonial period.

The Struggle for Survival and Resistance

Despite these challenges, the Worimi people demonstrated remarkable resilience. Many maintained their cultural practices in secret, passing down knowledge through oral traditions and preserving their connection to the land even as it was being taken from them.

Instances of resistance were recorded, with some Worimi individuals actively opposing colonial expansion through physical confrontation or by guiding their communities to safer areas. Others worked within the colonial system to advocate for Aboriginal rights, ensuring their voices were heard despite systemic oppression.

The forced assimilation policies of the 20th century, including the Stolen Generations, further disrupted Worimi families. Children were removed from their homes and placed in institutions, where they were forbidden to speak their language or practice their culture. These policies inflicted lasting trauma but also ignited a renewed determination to preserve and revitalise Worimi heritage in later generations.

Contemporary Worimi Community

Modern Initiatives for Cultural Preservation

Today, the Worimi people are actively reclaiming and preserving their cultural heritage through initiatives led by organisations such as the Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council. Established in the 1980s, this council works to protect sacred sites, support community well-being, and educate the broader public about Worimi history and traditions.

One of the council’s most significant achievements is the management of the Worimi Conservation Lands, which include the famous Stockton Bight Sand Dunes. These lands are not only a popular tourist destination but also a vital cultural site for the Worimi people. Guided tours led by Worimi custodians offer visitors an opportunity to learn about Dreaming stories, traditional land management practices, and the significance of the dunes (Worimi Conservation Lands).

Education is another key focus. Programs in local schools and community centres teach the Gathang language, traditional storytelling, and sustainable practices, ensuring that Worimi knowledge is passed down to future generations. Partnerships with universities and research institutions have further amplified efforts to document and share Worimi culture.

Worimi Art and Storytelling

Traditional and Contemporary Worimi Art

Art has always been a vital form of expression for the Worimi people, capturing their connection to the land, spirituality, and traditions. Traditional Worimi art often uses natural pigments like ochre and charcoal to create earthy tones that reflect the coastal landscapes, sand dunes, and waterways of their homeland. These works frequently incorporate symbols of nature, such as fish, birds, and trees, each carrying specific cultural meanings.

One prominent example of Worimi art is the carvings and engravings found on rocks within the Stockton Bight Sand Dunes. These carvings depict animals, spiritual figures, and geometric patterns, serving as both storytelling tools and markers of sacred spaces.

Contemporary Worimi artists continue this tradition, blending ancestral designs with modern techniques. For example, artist Debbie Becker, a proud Worimi woman, is known for her intricate dot paintings and depictions of marine life, reflecting the coastal essence of her heritage. The Saltwater Freshwater Arts Alliance frequently features Worimi artists, highlighting works that explore themes of identity, connection, and resilience (Saltwater Freshwater Arts).

Dreamtime Storytelling and Its Significance

Dreamtime stories are an integral part of the Worimi people’s cultural framework, explaining the creation of the land, its features, and the laws of nature. These oral traditions are both spiritual teachings and moral lessons, guiding individuals on how to live harmoniously with the environment and each other.

A famous Dreamtime story involves the creation of the Stockton Bight Sand Dunes, a sacred site for the Worimi people. The story recounts how ancestral spirits moved across the land, shaping the dunes with their footprints and imbuing them with spiritual energy. This narrative teaches the importance of respecting sacred landscapes and the spirits that reside within them.

Another Dreamtime story centres on the Willy Wagtail (gitjarrgitjarr), considered a messenger and guide. According to the tale, the bird warns of approaching danger and helps navigate troubled times. This story serves as a reminder of the interconnectedness of all living things and the importance of paying attention to the natural world.

These stories are shared during community gatherings, ceremonies, and educational workshops. Elders ensure they are passed down to younger generations, preserving the Worimi people’s values and cultural identity.

Connection to Buttaba and Lake Macquarie

Buttaba on Shared Lands

The suburb of Buttaba, located on the western shore of Lake Macquarie, is a place of shared cultural and spiritual significance for both the Worimi and Awabakal peoples. The name Buttaba is believed to have Aboriginal origins, though its exact meaning remains unclear. For thousands of years, this land served as a vital resource hub, offering an abundance of fish, shellfish, and other marine life from the lake’s calm waters.

Lake Macquarie, known as Awaba to the Awabakal people, also holds spiritual significance for the Worimi. While primarily associated with the Awabakal Nation, the lake was part of trade routes and cultural exchanges between the two groups. Areas like Buttaba, with its fertile wetlands and diverse wildlife, symbolise the interconnectedness of these neighbouring nations and their shared commitment to caring for the land.

Lake Macquarie And the Worimi People

For the Worimi, Lake Macquarie was more than a source of food—it was a sacred site deeply woven into their stories and traditions. The lake and its surrounding areas provided materials for crafting tools, such as shells and stones, which were used for fishing and hunting. Campsites around the lake, marked by ancient shell middens, highlight its enduring role in the daily lives of the Worimi people.

The lake also features in spiritual teachings, including Dreamtime stories that connect the water, land, and sky. These narratives emphasise the balance between taking from the land and giving back, teaching future generations the importance of sustainability and respect.

Today, Buttaba and Lake Macquarie continue to hold cultural and historical importance. Conservation initiatives and educational programs led by local councils and Aboriginal organisations aim to preserve the natural and cultural heritage of the region, ensuring its stories and traditions remain alive for all to learn from and appreciate.

Notable Sites and Cultural Landscapes

The Stockton Bight Sand Dunes

One of the most iconic cultural landscapes associated with the Worimi people is the Stockton Bight Sand Dunes. Stretching over 32 kilometres, these dunes form the largest moving sand system in the Southern Hemisphere. The dunes hold deep spiritual and cultural significance, as they are believed to have been shaped by ancestral spirits during the Dreaming.

The dunes are not only a sacred site but also a testament to the Worimi people’s sustainable practices. The area provided resources such as shellfish and bush foods, while its proximity to the ocean supported fishing and trade. Today, the dunes are part of the Worimi Conservation Lands, managed collaboratively by the Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council and government organisations. Visitors can participate in guided tours led by Worimi custodians, learning about the history, Dreamtime stories, and environmental significance of the site (Worimi Conservation Lands).

Port Stephens and the Great Lakes

Port Stephens, a key location within Worimi territory, is another area rich in cultural significance. The estuaries and waterways served as vital resources for fishing, gathering shellfish, and crafting tools from natural materials. The region was also a hub for trade, connecting the Worimi people with neighbouring nations like the Awabakal and Birpai.

The Great Lakes region, including Forster and Tuncurry, reflects the Worimi people’s connection to the water. These areas are known for their biodiversity, providing fish, crabs, and native plants that were central to the Worimi diet and medicine. Stories tied to the lakes often highlight the importance of balance and sustainability, ensuring that these resources were never depleted.

Sacred Sites and Conservation Efforts

Sacred sites within Worimi land, such as ceremonial grounds and burial sites, are integral to their spiritual heritage. These sites are protected under Aboriginal cultural heritage laws, but ongoing conservation efforts are essential to ensure they remain undisturbed. The Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council works closely with local governments to safeguard these areas and promote awareness of their significance.

Visitors to Worimi land are encouraged to approach with respect, understanding that these landscapes are more than scenic attractions—they are living histories that continue to connect the Worimi people to their ancestors.

The Impact of Colonisation

The colonisation of Worimi land brought profound challenges to the Worimi people, fundamentally altering their way of life. From the late 18th century onward, British settlers claimed large tracts of land, disrupting traditional practices and severing spiritual connections to the environment. The establishment of the Australian Agricultural Company (AAC) in the early 19th century displaced many Worimi communities, forcing them to move away from their ancestral lands around Port Stephens and other key areas.

Diseases like smallpox and influenza, introduced by European settlers, devastated the population, which had no immunity to these illnesses. Combined with the loss of land, food sources, and autonomy, these factors caused significant declines in the Worimi population and their cultural practices.

The Stolen Generations

One of the most painful legacies of colonisation for the Worimi people, and Aboriginal Australians more broadly, was the Stolen Generations. Between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries, government policies forcibly removed Aboriginal children from their families to assimilate them into white society. These children were placed in institutions or foster homes, where they were often forbidden to speak their language or practice their culture.

For the Worimi people, this trauma led to the loss of knowledge, traditions, and a sense of identity. However, the resilience of the community is evident in the efforts of survivors and their descendants to reclaim their heritage.

Revitalisation and Advocacy

Despite these challenges, the Worimi people have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Efforts to revitalise their language, culture, and traditions have gained momentum in recent decades. Programs led by the Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council, along with broader national initiatives, have created pathways to preserve their heritage.

The management of the Worimi Conservation Lands, including the Stockton Bight Sand Dunes, serves as an example of how Worimi people are reclaiming stewardship of their ancestral lands. Cultural education programs in schools and community workshops also ensure that younger generations can reconnect with their roots.

Building Toward the Future

While the effects of colonisation remain a part of the Worimi people’s story, their ability to adapt and thrive showcases their strength. Today, they continue to advocate for their rights, protect sacred sites, and share their culture with the broader community. This resilience ensures that the traditions and wisdom of the Worimi people will endure, offering lessons in sustainability, community, and respect for the land.

With Respect to the Worimi People

Writing about the Worimi people and their enduring connection to the land has been a deeply reflective experience. The stories, traditions, and resilience of this community offer valuable insights into the history of Australia and how we interact with the environment.

When visiting places like the Stockton Bight Sand Dunes or the Great Lakes, the significance of these sites to the Worimi people becomes strikingly clear. These are not just beautiful landscapes—they are living connections to a culture that has cared for this land for thousands of years. For me, learning about the Dreamtime stories tied to these places, like the formation of the dunes by ancestral spirits, has deepened my understanding of the Worimi people’s spiritual relationship with the land.

Buttaba, where the Worimi and Awabakal lands overlap, is another example of how history and culture intertwine. Seeing how these two nations cooperated and shared resources over millennia inspires respect for their values of reciprocity and care. It’s also a reminder of the cultural losses endured during colonisation, and the importance of ongoing efforts to support Aboriginal communities in reclaiming their heritage.

One of the most striking aspects of the Worimi people’s story is their ability to preserve their identity through challenges like displacement and the Stolen Generations. Their efforts to revitalise the Gathang language, protect sacred sites, and educate future generations demonstrate a remarkable commitment to cultural survival.

Personally, visiting Worimi Conservation Lands and engaging with local Aboriginal leaders has reinforced the importance of reconciliation. It’s not just about recognising the past—it’s about actively supporting the Worimi people’s vision for the future. Whether it’s by supporting initiatives like the Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council or simply listening and learning from their stories, there are many ways to honour their legacy and contribute to their ongoing journey.

The Worimi people’s connection to the land is not just their heritage—it’s a lesson for all of us. By respecting their traditions and understanding their stories, we can begin to build a more inclusive and respectful society.

The Worimi People and Buttaba

1. Who are the Worimi people?

The Worimi are the Traditional Custodians of a large area in coastal New South Wales, encompassing land from the Hunter River in the south to the Manning River in the north, and westward to the Barrington Tops. Their culture, history, and connection to the land span at least 11,000 years, making them one of the oldest continuous cultures in the world.

2. What is the significance of Buttaba to the Worimi and Awabakal peoples?

The suburb of Buttaba, located on the shores of Lake Macquarie, lies on land of shared custodianship between the Worimi and Awabakal peoples. This area was significant for fishing, hunting, and ceremonies, reflecting the collaborative relationship between these two nations and their connection to the lake, known as Awaba in Aboriginal language.

3. What are some Dreamtime stories of the Worimi people?

The Worimi people’s Dreamtime stories explain the creation and spiritual significance of their lands. For example, the Stockton Bight Sand Dunes were said to have been shaped by ancestral spirits. The Willy Wagtail (gitjarrgitjarr) is another central figure in their stories, symbolising guidance and protection. These tales carry lessons about respect, balance, and sustainability.

4. What is the Gathang language, and how is it being preserved?

The Gathang language is traditionally spoken by the Worimi, Birpai, and Gringai peoples. Efforts to revitalise the language include educational programs, dictionaries, and workshops led by the Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council. These initiatives ensure that younger generations can reconnect with their linguistic heritage.

5. How can I support the Worimi community today?

You can support the Worimi community by visiting the Worimi Conservation Lands, participating in guided cultural tours, and learning about their history and traditions. Supporting organisations like the Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council or attending cultural festivals such as the Saltwater Freshwater Festival are also great ways to contribute to preserving and celebrating Worimi heritage.